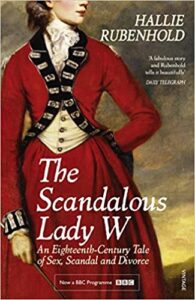

The Scandalous Lady W: An Eighteenth-Century Tale of Sex, Scandal, and Divorce

by Hallie Rubenhold

Review by jjares

The famous Joshua Reynolds created the portrait of Lady Worsley on the cover of this book. The riding habit is adapted from her husband’s regiment. Seymour Fleming married Sir Richard Worsley when she was 17, and the marriage fell apart quickly. Once Richard got an heir, he lost interest in his wife. Because his wife brought a great deal of money to the marriage (~ 52,000 pounds), Richard could concentrate on things that interested him, including his seat in the House of Commons, his military pursuits for protecting his lands from French invasion, and belonging to two famous groups — the Society of Antiquaries of London and the Royal Society. Unfortunately, they did not include Lady Seymour. To retaliate, Lady Seymour had many lovers.

The couple had one son, Robert Edwin (1776 – 1795), and Richard claimed paternity of Seymour’s daughter, Jane Seymour Worsley, to avoid scandal. However, George M Bissett was the child’s father. Wanting to be together, Bissett and Lady Seymour ran away together late in 1781. Richard begged his wife to return home, but she refused. The following year, Richard brought a ‘Criminal Conversation’ case against Bissett for 20,000 pounds, an incredible amount of money at the time.

This court case raised eyebrows and fed the rumor mills for a long time. ‘Criminal Conversation’ was the court’s title for the husband suing the man at fault for stealing his wife’s affections. Richard refused to get a divorce; he wanted to make the couple suffer. So he sued Bissett for a ruinous amount of money and washed his hands of his wife by refusing to give Lady Seymour her clothing or pay her bills (which eventually led her to become a kept woman by rich and powerful men). Lady Seymour turned the tables on Richard by asking some of her previous lovers to come to court and explain that Richard never contested her behavior — and, in some instances, aided and abetted it. She also encouraged her physician to go to court and explain Lady Seymour got the venereal disease from one of her paramours.

I will leave you to read the book to find out how the court case ended. However, in 1788, the couple entered into ‘Articles of Separation,’ which did not allow Lady Seymour to marry Bissett (until after her husband’s death). By the end of the court case, all the parties were socially ruined. Their story continued in the newspapers for months in rhyme, illustration, and prose. Finally, Seymour realized that humiliating her husband was her only recourse (to retrieve her clothing, etc.), and the public ate it up. Richard went into hiding, and Seymour paraded herself to humiliate him further. Incredibly, before it was all over, the couple wrote about their problems for all to read in the newspapers. Eventually, Lady Worsley and Captain Bissett separated. Bissett’s brother was entering religious orders, and he pressured his brother to cease the scandalous liaison. Captain Bissett married another, inherited property, and became a highly-regarded gentleman by the time of his death.

Lady Worsley was forced to become a professional mistress to survive. The book points out that a substantial group of upper-class women were in the same position. Women could not divorce their husbands because English law saw them as mere possessions of their husbands. Richard was so humiliated that he escaped on a world tour, and to redeem his reputation as an antiquarian scholar.

Lady Seymour had two more children. There was a second child with Bissett. Nothing more is known of the child. Seymour escaped to France, where infidelity was well-tolerated. She returned to England to have her fourth child, a girl, who was given to a farm family to raise (a common way to shed unwanted children amongst the aristocracy).

Part of her final separation decree stated that she must reside outside England for four years. If she returned before that time, she would forfeit the money her husband had settled on her. Unfortunately, the French Revolution occurred, and Lady Seymour was probably imprisoned during some of that time. She begged her husband’s solicitors to allow her to return to England because of the danger. However, they warned her of the consequences if she did so. Thus, she was in France when her son Robert died unexpectedly in England.

After Seymour returned to England, she was gravely ill for two months. Her mother, sister, and husband came to visit her. Seymour was relieved when her family forgave her and people saw them in her company. Meanwhile, Richard returned to Europe and invested in many antiquities. Unfortunately, Bonaparte commandeered them, causing a total loss to Richard. Richard was in financial straits with this loss and the tremendous expenses of court cases, and Seymour’s expensive lifestyle.

Richard retired to the Isle of Wight and had a relationship with a person listed as Richard’s housekeeper — Mrs. Sarah Smith. She stayed with him until his death. With Richard’s death, Seymour’s wealth reverted to her. One month after Richard’s death, forty-seven-year-old Seymour marched down the aisle with twenty-six-year-old John Lewis Cuchet. By royal license, Seymour took back her maiden name ‘Fleming’ and John took it as his surname too.

Eventually, Seymour and John moved back to Passy (France), where she died in 1818 (~ 61 years of age). Despite their age differences, the author claims that John Lewis was the only man to understand Seymour. He married again (1 and a half years later) but asked to be buried next to his first wife.

After starting this book, I learned that the BBC made a film based on this book in 2015. The author may have included too much detail, but there is no doubt that this is a fascinating story of infidelity in the 1700s.